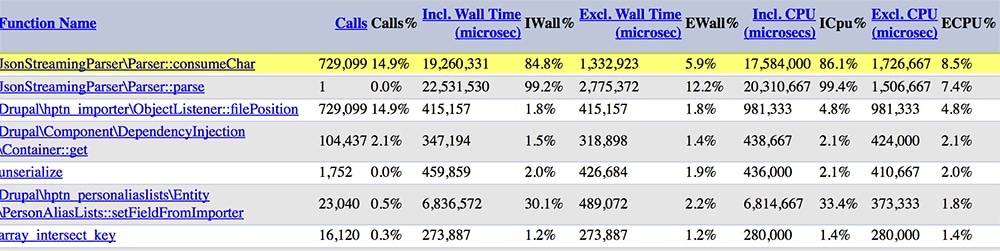

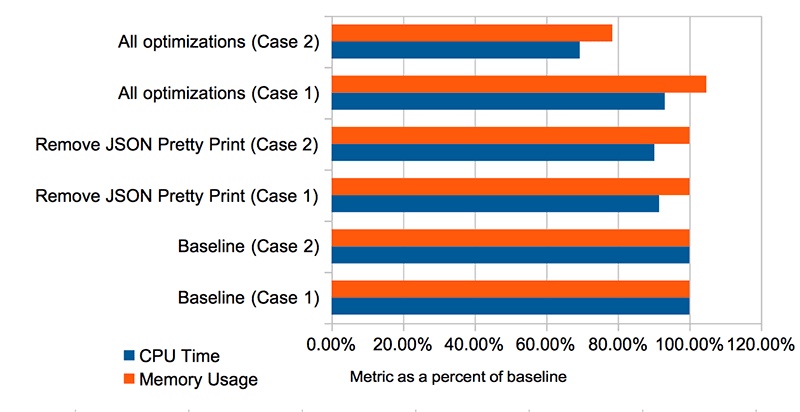

It turns out that the JSON files I was importing were pretty-printed, thus containing more whitespace than they needed to. Sine the consumeChar method gets called on each incoming character of the input stream, that added up to a lot of unnecessary method calls in the original code. By tweaking the JSON file export code to remove the pretty print flag, I cut down the number of times this method was called from 729,099 to 499,809, saving .2 seconds of run time right off the bat.

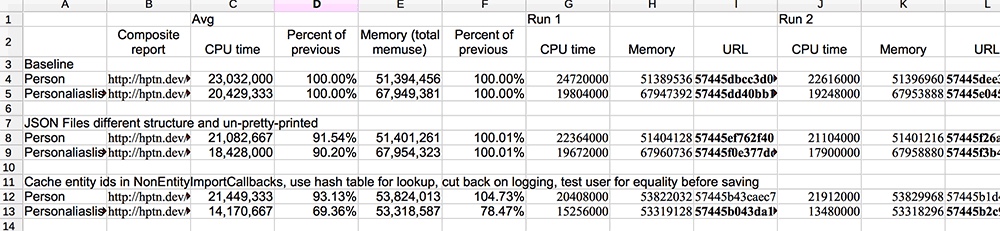

That was the major place where the XHProf profiler report gave me insights I would not have had otherwise. The rest of my optimizing experience was mostly testing out some of the common-sense optimizations I had already thought of while looking at the code – caching a table of known Entity IDs rather than querying the DB to check if an entity existed each time, using an associative array and is_empty() to replace in_array() calls, cutting down on unnecessary $entity->save() operations where possible.

It’s useful to mention that across the board the biggest performance hit in your Drupal code will probably be database calls, so cutting down on those wherever possible will save run-time (sometimes at the expense of memory, if you’re caching large amounts of data). Remember, also, that if DB log is enabled each logging call is a separate database operation, so use the log sparingly – or just log to syslog and use service like Papertrail or Loggly on production sites.