There are many good online tutorials that cover Git merging, so I’ll just review the basics. If you’re already fluent in Git, feel free to skip to the strategies and tools section.

As Atlassian’s branching tutorial explains “Merging is Git’s way of putting a forked history back together again.”

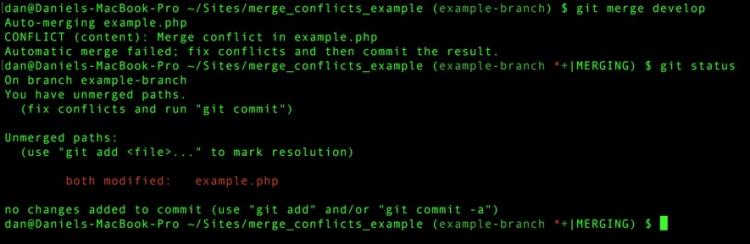

A Git merge is run via the command git merge <target_branch>. When merging, Git always merges into the current branch. The branch being merged (aka the target branch) will not be affected.

There are two types of merges: fast-forward merges and 3-way merges.

Fast forward merges occur when the tip of the current branch is a direct ancestor of the target branch. In this case, instead of actually merging the branches, Git simply moves (or fast forwards) the current branch tip up to the target branch tip.

However, a fast-forward merge is not possible if the branches have diverged. In those cases, a 3-way merge is required, which uses a dedicated commit to bring together the two histories.

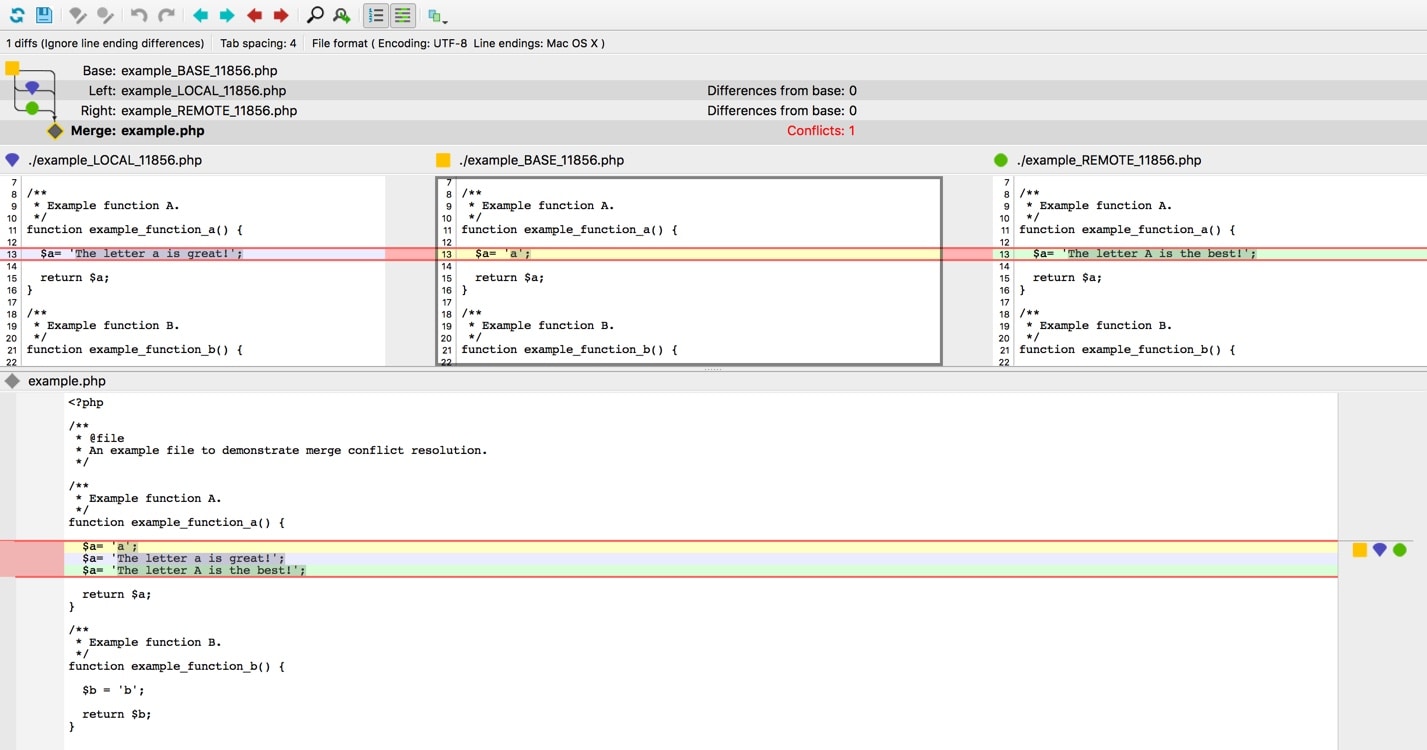

In a three way merge, Git’s merge algorithm uses the current branch, the target branch, and their merge base in order to incorporate changes from the target branch into the current branch. The merge base is essentially the most recent common ancestor (often this is the commit before the two branches forked). Git uses the merge base to identify what changed since the branches diverged.

Git is smart, and non-overlapping changes (areas of code modified by one branch but not that other) are automatically incorporated into the final merged result. However, sometimes both branches change the same part of the same file, resulting in merge conflicts.